Click HERE to read Svetlana Bachenova's interview about this project featured on FotoEvidence.

Two years ago I photographed a series of protests in Yerevan with the mothers and fathers of soldiers who had died in mysterious noncombat circumstances while completing their two years of compulsory military service in Armenia.

The legal system had failed to uncover what happened to their sons. For these families, the entire system seemed to be conspiring against the truth.

Human rights organizations estimate the number of noncombat deaths since Armenia's armed forced were established to be between 1500 and 3000. (Source: Helsinki Citizens' Assembly)

A group of soldiers' mothers stand in front of the government building at Yerevan's Republic Square every Thursday morning at 11am holding their sons' photographs and demanding that their cases be handled justly.

Cradling her deceased son Valery's photograph, Nana Muradyan stands in front of the government building in Yerevan where she and other mothers protest the unsolved crimes committed against their sons during their mandatory military service.

I visited Nana Muradyan twice at her home and both times she was alone. Her home was immaculate, everything perfectly in its place.

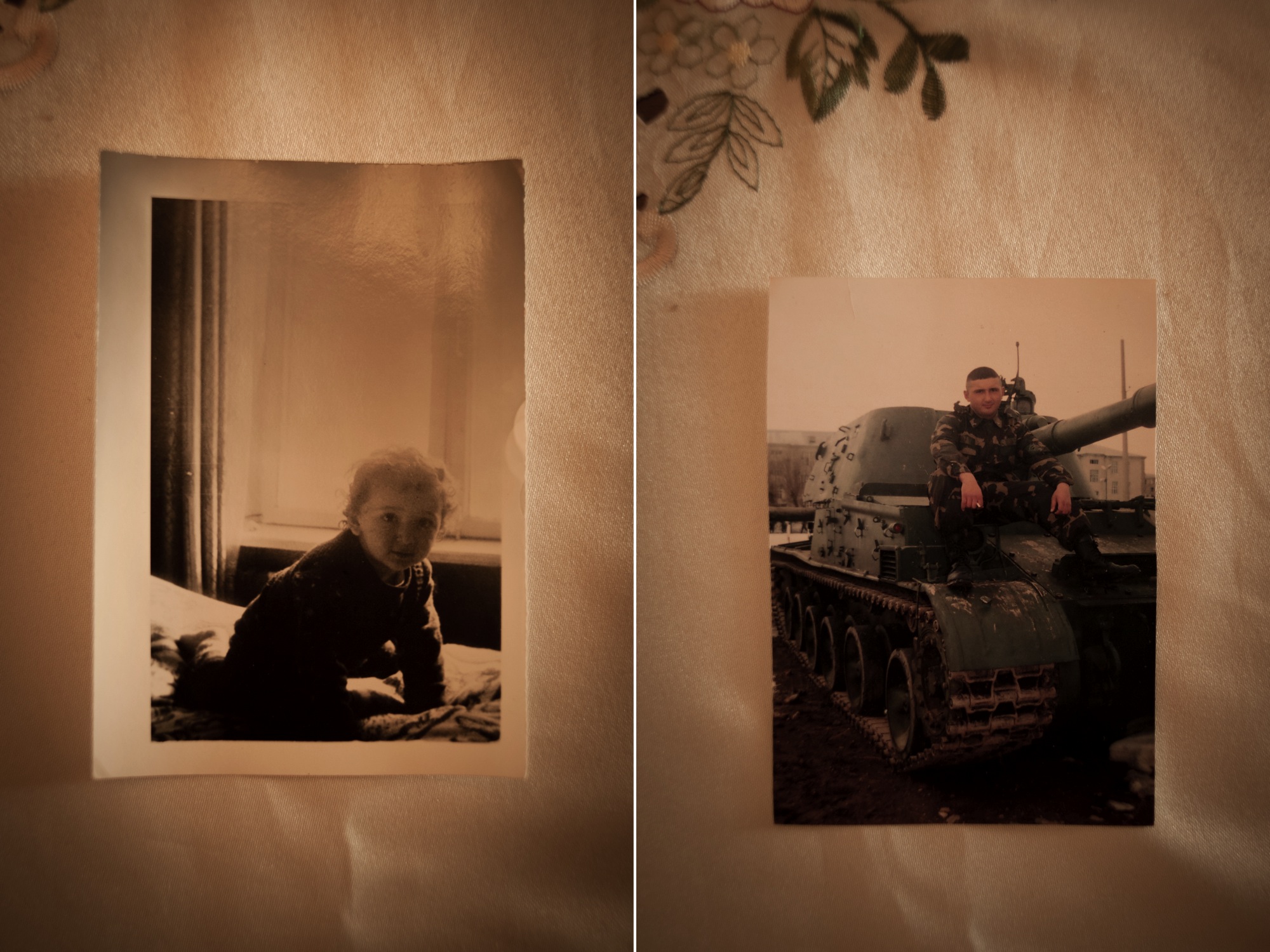

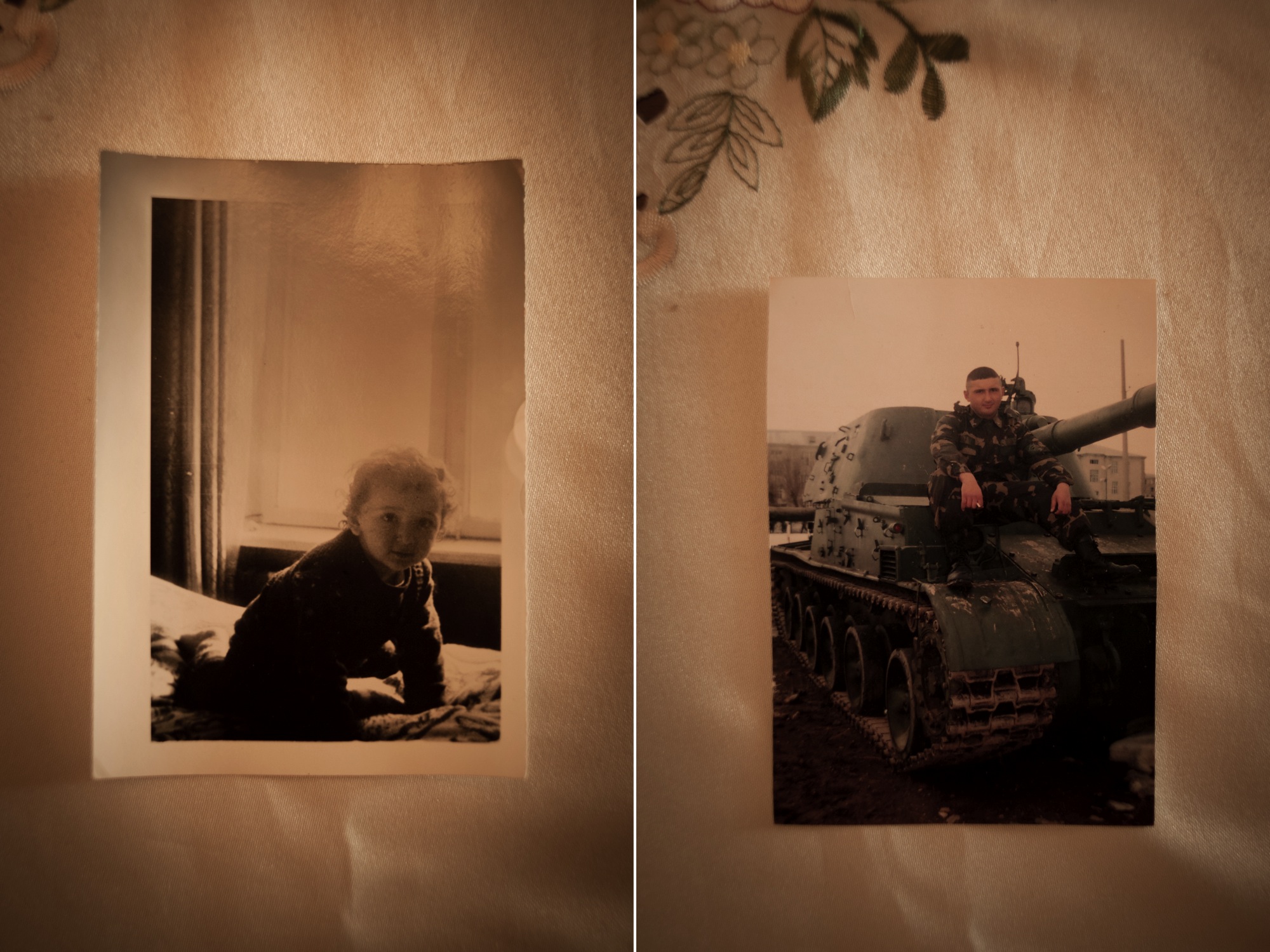

Nana's son Valery loved being a soldier. The family had decided to leave Armenia after his military service but Valery had convinced them to stay so that he could become a contract officer.

In 2010, Valery's body was found hanging from a metal pipe at the military base where he was serving. The military says he committed suicide, Valery's family believes their son was killed and the suicide staged to cover up the murder.

Nana examines her son Valery's autopsy photos. She recounted having received a phone call from him several days before the incident, he had witnessed military personnel stealing fuel from the base and was offered 3000 dram ($7) to stay quiet.

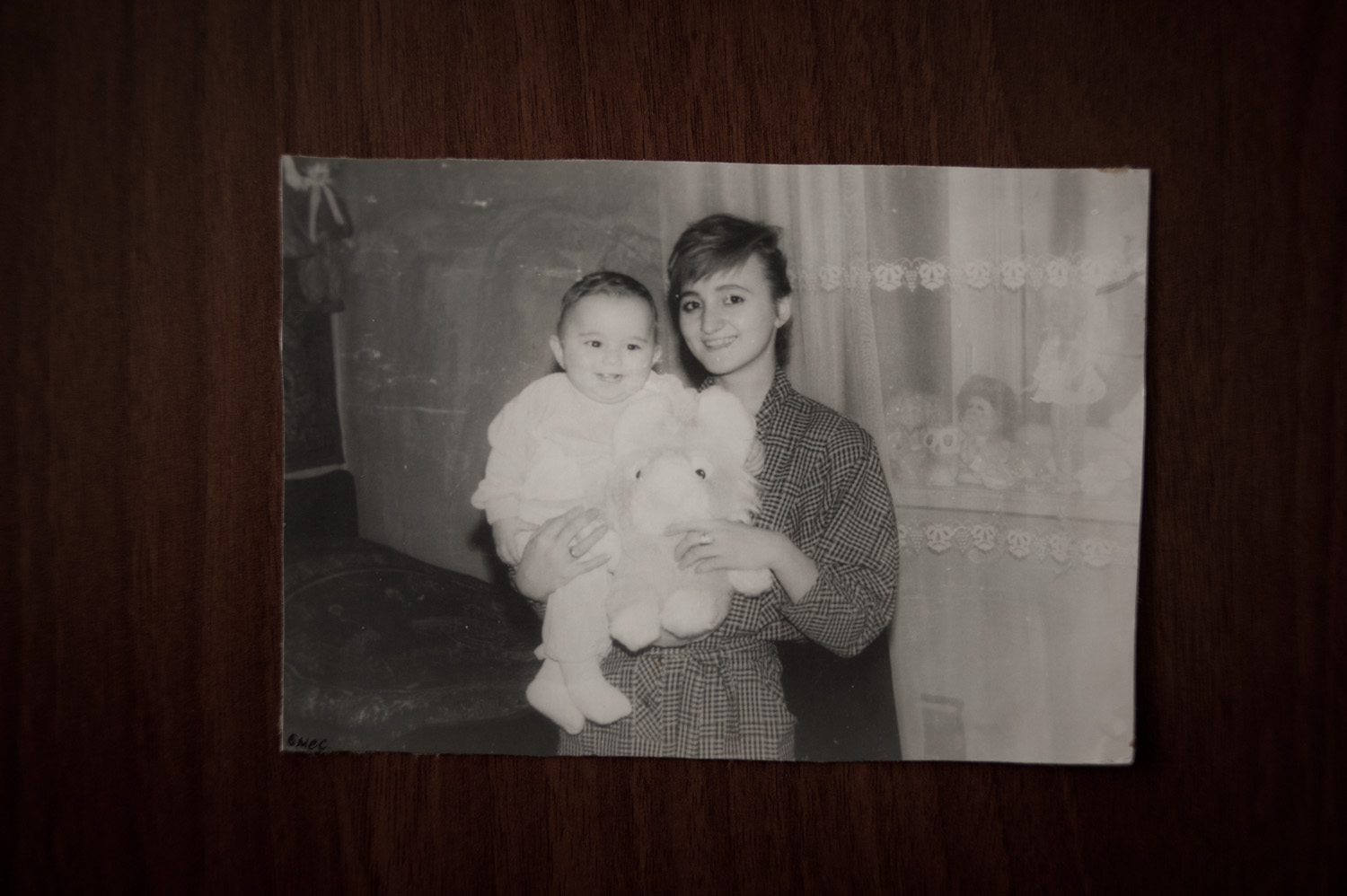

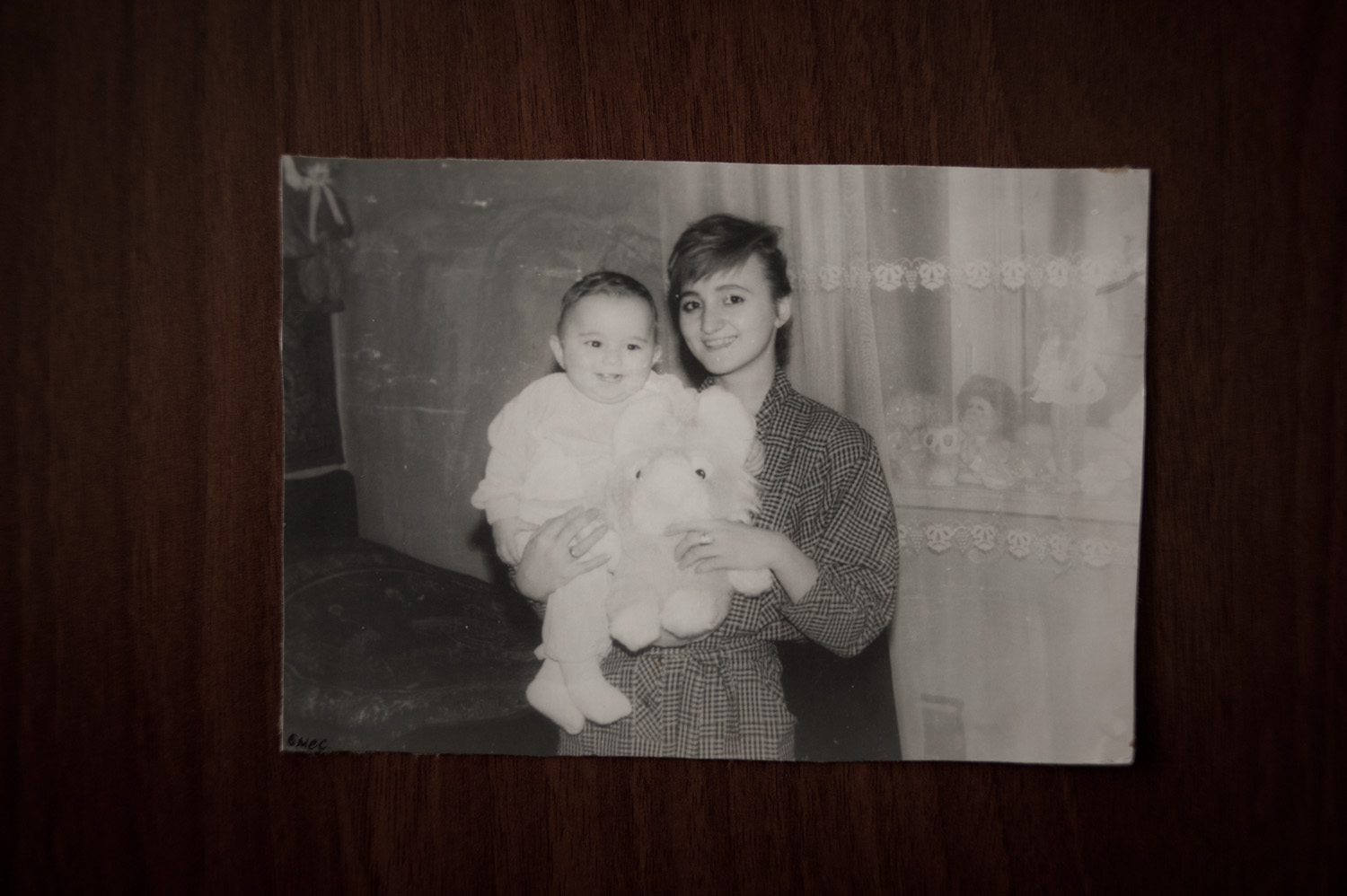

Nana with baby Valery. She believes her son's death was related to his having witnessed the fuel theft.

"When we realized that our son's murder was being covered up, we decided to take our son's body out of the ground in protest and put it in Republic Square. Our whole neighborhood came out with shovels in hand. But we were talked out of it with more promises that justice would prevail."

"My son and daughter slept in the same room, on two beds at opposite sides of the room. Now that my son's bed is empty, my husband, daughter and I will often sit or lie on it - it is the place where we feel closest to him."

No military personnel have been held responsible for Valery's death. Nana and her family continue to seek justice: "If all the mothers whose sons have died like this join us, we would fill this entire square with mothers in black."

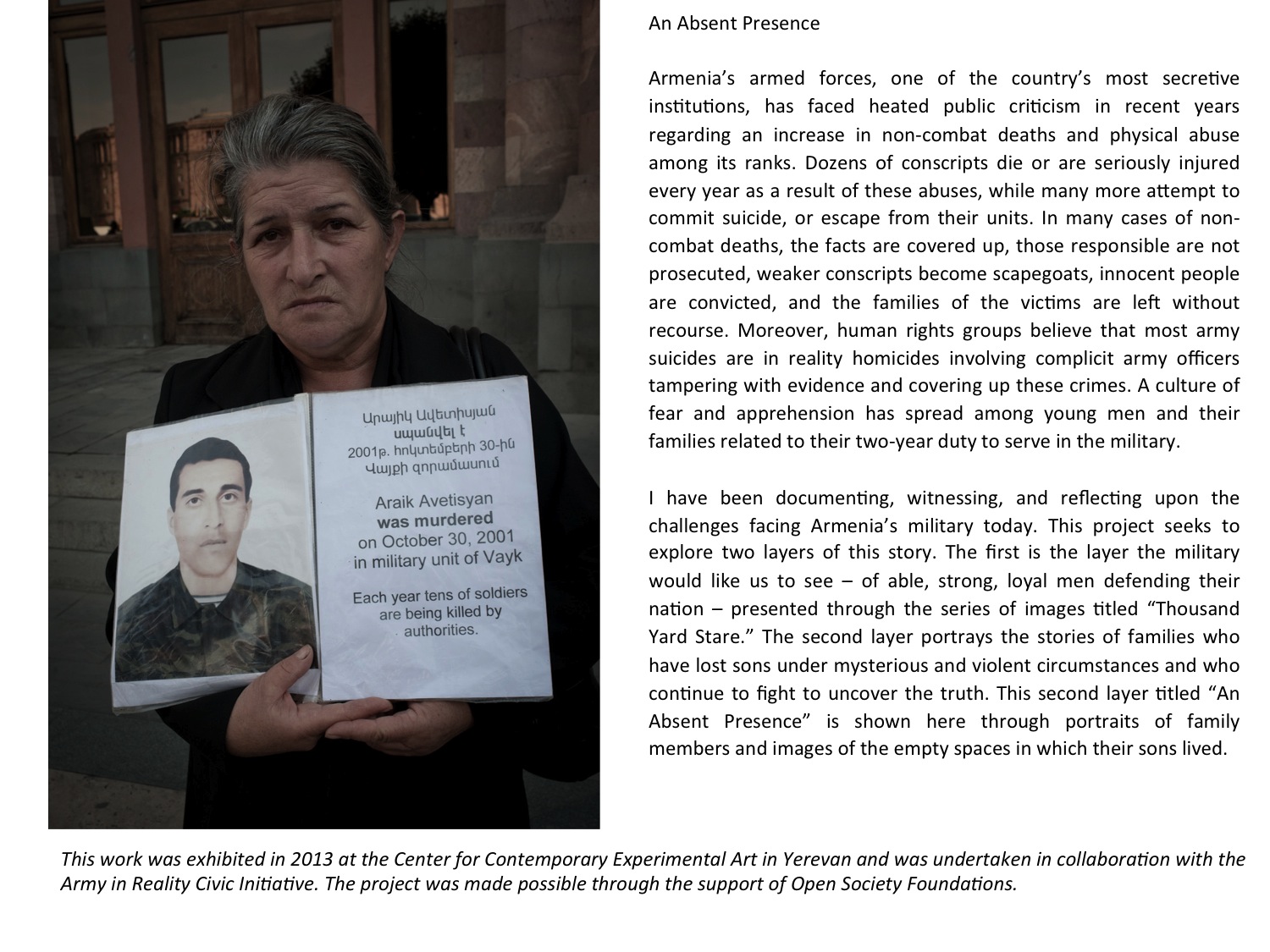

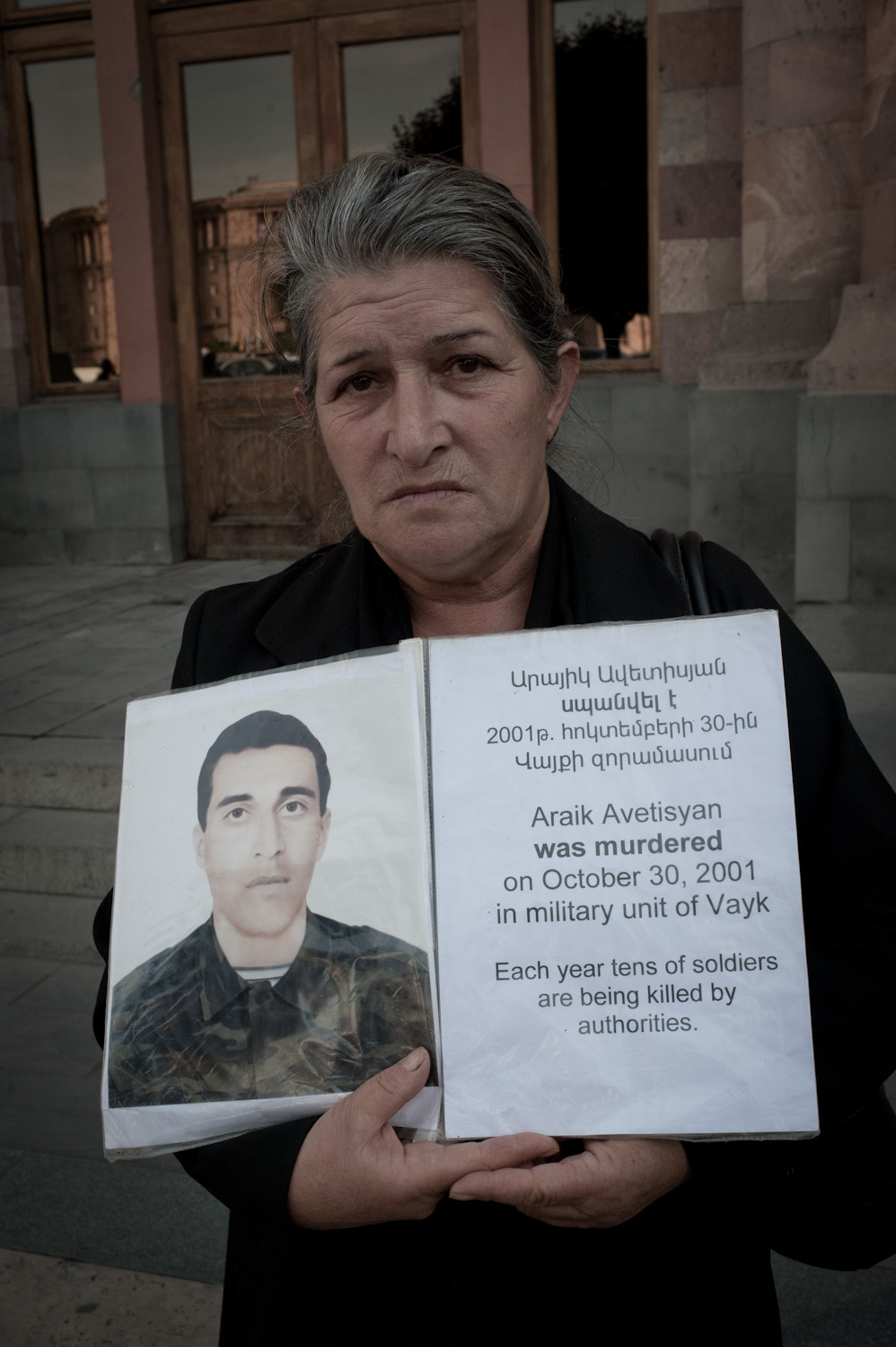

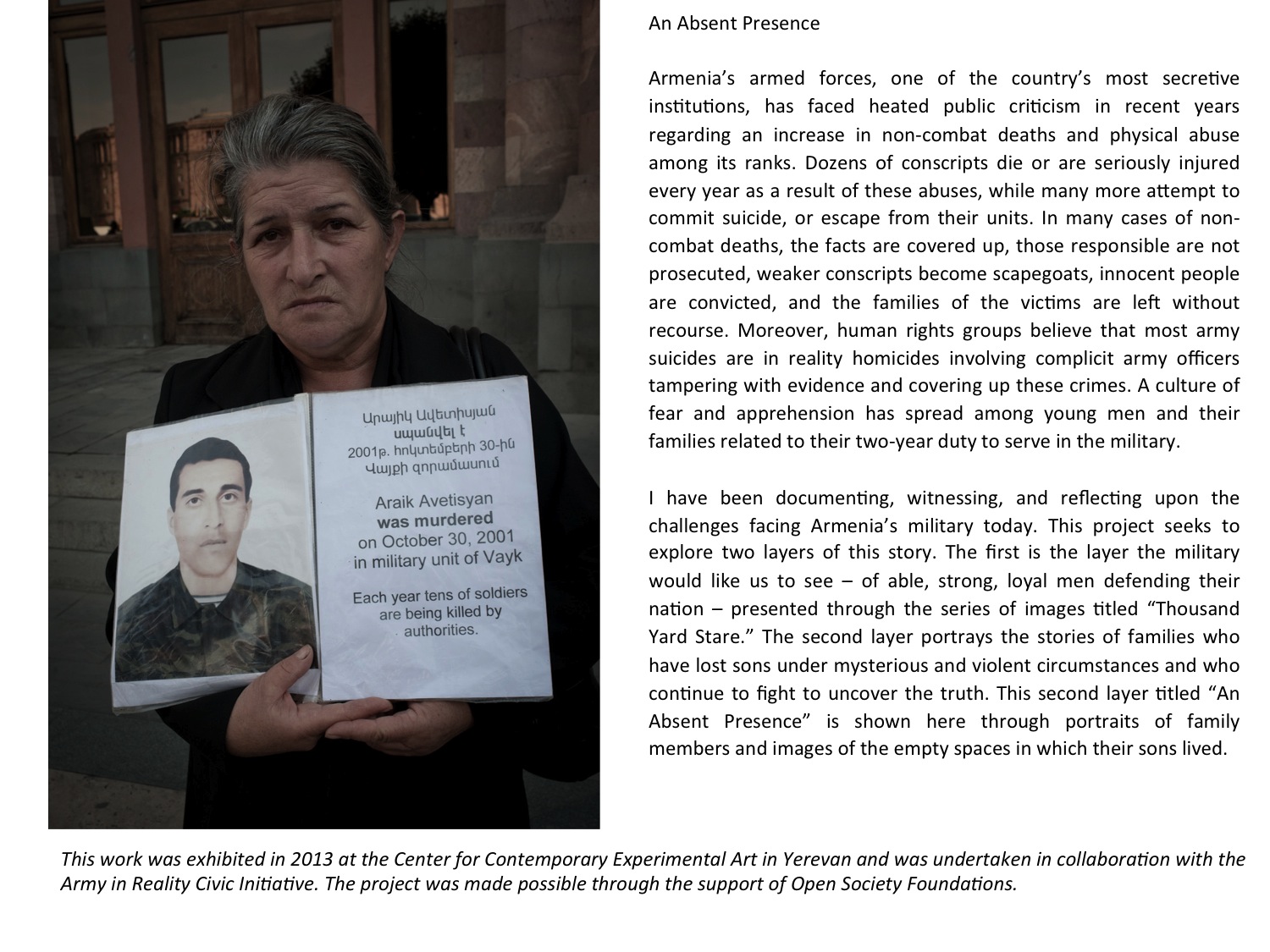

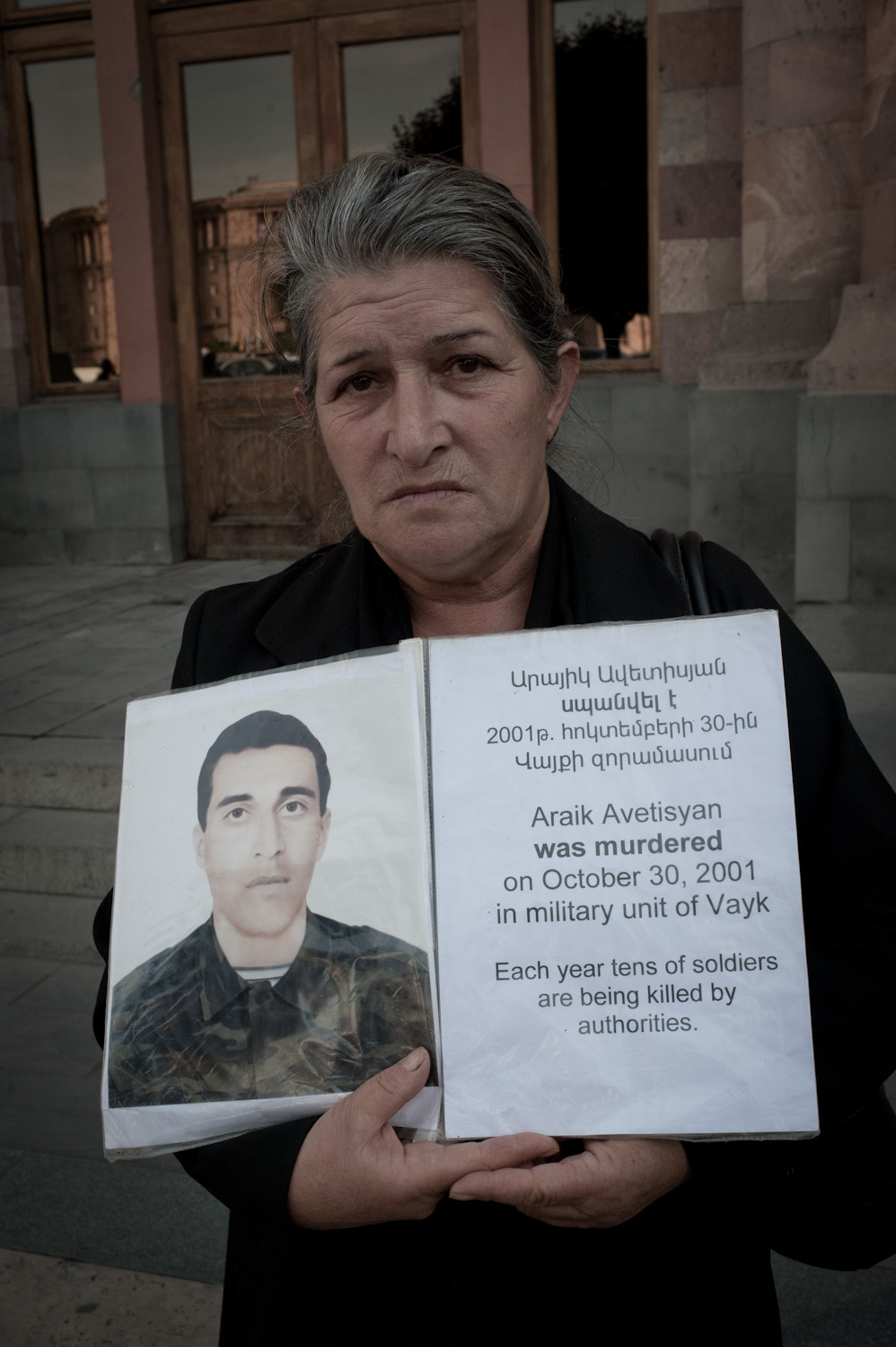

Anahit Avedisyan's son Araik was killed in 2001 - shot point blank in the head. The Avedisyan family believes that Araik's battalion commander while drunk, shot Araik for paying him only half of the $100 he had demanded for allowing Araik to take leave to visit his family.

Anahit and Aghasi at their son's grave. "While serving, my son would describe how the battalion commander would grab soldiers by the collar and put his loaded gun to their heads to scare them. This is the same way my son was killed."

Other parents with sons at the same military base as Araik told the Avedisyans that they would send $100 per month to the commander as an "insurance policy" for their sons' well being.

Araik Avedisyan's bedroom. "I overheard a conversation my grandchildren were having the other day," Anahit recalled, "my granddaughter Ani asked my grandson Ara what he wants to be when he grows up. Ara said 'a soldier' and Ani responded 'Don't be a soldier, they leave and never come back.'"

Araik's mother keeps a tuft of her son's hair from his childhood.

Another soldier admitted to accidentally killing Araik while handling a loaded gun - the Avedisyans believe that the admission was coerced in order to protect the battalion commander.

The Avedisyans case is now being considered by the European Court of Human Rights. "Everyone knows what happened to my son. Once I saw a group of men from our village getting ready to board a bus to begin their military service. We locked eyes and it was as if they were asking me 'will we come back?'"

Irina Ghazaryan's son Arthur died in 2010 during his military service. The military contends that the nineteen year old died of a brain tumor. The Ghazaryans believe their son was killed.

Arthur's parents Smbat and Irina sit beneath their son's portrait sifting through case files, paperwork and autopsy photographs related to their son's death.

Irina: "My husband was so proud to have 3 sons all of whom served in the military. But since my son's death, he is so angry, that he often says that should there be a war he will kill several of our commanders before lifting a finger against the enemy."

Irina: "On December 14 Arthur called from the base, he said that one of the commanders was running a narcotics business. I told him to be quiet and not talk about these things on the telephone."

Irina: "For three days after that phone call, I could not get a hold of my son. I have no idea what happened during those three days. Then they called us with the news that Arthur was taken to the hospital."

Irina's three sons all slept in the same room together. They have not removed the third bed from the room since his death.

Arthur's home. The military contends that Arthur died of a brain tumor. Irina and Smbat suspect foul play related to the narcotics story their son recounted. Among other inconsistencies during the investigation, the autopsy did not produce a tumor.

Gohar Ohanjayan's son Tigran died in 2007 while serving. During his last three months of service he complained that the commanders would hit him. The military says Tigran ran into a live wire and was electrocuted. The Ohanjanyan family believes their son was killed.

Gohar: "My son Tigran was born in 1988. I remember lying in the hospital listening to the hundreds of thousands of people outside demanding Armenia's independence from the Soviet Union."

Gohar: "My son was 12 when we decided to move to Russia. We could not make ends meet here in Armenia. One day Tigran saw Armenia's defense minister on TV talking about military service. That's when he decided to return to Armenia to serve."

While serving, Tigran recounted that a younger, weaker soldier was being hazed by the officers and was hit. Tigran had stepped in and criticized the officers. The Ohanjanyans believe their son's death was related to this incident.

Tigran's bedroom. Gohar: "Since we were in Russia, our family members would visit Tigran at the base. On August 22 they noticed once that his eye was bruised and bloodied and that his fists were damaged. Eight days later our son was dead."

Tigran was a skilled judoist and had received numerous medals and accolades in judo.

Tigran's boxing gloves.

The Ohanjanyan family home.

Tigran's judo medals.

A year after Tigran's death, Tigran's father (left) was attacked twice by a group of men who hit him and warned him to stop protesting his son's death.

Gohar: "It's so hard not to know what happened to my child." Although the military's official position is that Tigran was accidentally electrocuted, no electricity was found in the area where he died. The Ohanjanyans continue to seek the truth in their son's case.

Meguerdich Meguerdichian sits next to the bed where his son Jora died in 2012. While serving at the Yeghnikner military base, Jora was severely beaten and fell into a coma. He later died at home in Lousakn village.

No one has been held responsible for Jora's death. The Meguerdichian family lives in abject poverty and has not received any aid from the government.

Jora's mother Gohar breastfeeding her youngest child. Jora was her eldest. She has four children remaining - two of them boys, who upon their eighteenth birthday will in turn be required to serve in the military.

To learn more or to get involved with the issue of non-combat deaths in Armenia, please connect with the following people/organizations: Lala Aslikyan, Tsovinar Nazaryan - Army in Reality Civic Initiative | Zhanna Alexanyan - Journalists for Human Rights | Sona Ayvazyan - Transperancy International

Click HERE to read Svetlana Bachenova's interview about this project featured on FotoEvidence.

Two years ago I photographed a series of protests in Yerevan with the mothers and fathers of soldiers who had died in mysterious noncombat circumstances while completing their two years of compulsory military service in Armenia.

The legal system had failed to uncover what happened to their sons. For these families, the entire system seemed to be conspiring against the truth.

Human rights organizations estimate the number of noncombat deaths since Armenia's armed forced were established to be between 1500 and 3000. (Source: Helsinki Citizens' Assembly)

A group of soldiers' mothers stand in front of the government building at Yerevan's Republic Square every Thursday morning at 11am holding their sons' photographs and demanding that their cases be handled justly.

Cradling her deceased son Valery's photograph, Nana Muradyan stands in front of the government building in Yerevan where she and other mothers protest the unsolved crimes committed against their sons during their mandatory military service.

I visited Nana Muradyan twice at her home and both times she was alone. Her home was immaculate, everything perfectly in its place.

Nana's son Valery loved being a soldier. The family had decided to leave Armenia after his military service but Valery had convinced them to stay so that he could become a contract officer.

In 2010, Valery's body was found hanging from a metal pipe at the military base where he was serving. The military says he committed suicide, Valery's family believes their son was killed and the suicide staged to cover up the murder.

Nana examines her son Valery's autopsy photos. She recounted having received a phone call from him several days before the incident, he had witnessed military personnel stealing fuel from the base and was offered 3000 dram ($7) to stay quiet.

Nana with baby Valery. She believes her son's death was related to his having witnessed the fuel theft.

"When we realized that our son's murder was being covered up, we decided to take our son's body out of the ground in protest and put it in Republic Square. Our whole neighborhood came out with shovels in hand. But we were talked out of it with more promises that justice would prevail."

"My son and daughter slept in the same room, on two beds at opposite sides of the room. Now that my son's bed is empty, my husband, daughter and I will often sit or lie on it - it is the place where we feel closest to him."

No military personnel have been held responsible for Valery's death. Nana and her family continue to seek justice: "If all the mothers whose sons have died like this join us, we would fill this entire square with mothers in black."

Anahit Avedisyan's son Araik was killed in 2001 - shot point blank in the head. The Avedisyan family believes that Araik's battalion commander while drunk, shot Araik for paying him only half of the $100 he had demanded for allowing Araik to take leave to visit his family.

Anahit and Aghasi at their son's grave. "While serving, my son would describe how the battalion commander would grab soldiers by the collar and put his loaded gun to their heads to scare them. This is the same way my son was killed."

Other parents with sons at the same military base as Araik told the Avedisyans that they would send $100 per month to the commander as an "insurance policy" for their sons' well being.

Araik Avedisyan's bedroom. "I overheard a conversation my grandchildren were having the other day," Anahit recalled, "my granddaughter Ani asked my grandson Ara what he wants to be when he grows up. Ara said 'a soldier' and Ani responded 'Don't be a soldier, they leave and never come back.'"

Araik's mother keeps a tuft of her son's hair from his childhood.

Another soldier admitted to accidentally killing Araik while handling a loaded gun - the Avedisyans believe that the admission was coerced in order to protect the battalion commander.

The Avedisyans case is now being considered by the European Court of Human Rights. "Everyone knows what happened to my son. Once I saw a group of men from our village getting ready to board a bus to begin their military service. We locked eyes and it was as if they were asking me 'will we come back?'"

Irina Ghazaryan's son Arthur died in 2010 during his military service. The military contends that the nineteen year old died of a brain tumor. The Ghazaryans believe their son was killed.

Arthur's parents Smbat and Irina sit beneath their son's portrait sifting through case files, paperwork and autopsy photographs related to their son's death.

Irina: "My husband was so proud to have 3 sons all of whom served in the military. But since my son's death, he is so angry, that he often says that should there be a war he will kill several of our commanders before lifting a finger against the enemy."

Irina: "On December 14 Arthur called from the base, he said that one of the commanders was running a narcotics business. I told him to be quiet and not talk about these things on the telephone."

Irina: "For three days after that phone call, I could not get a hold of my son. I have no idea what happened during those three days. Then they called us with the news that Arthur was taken to the hospital."

Irina's three sons all slept in the same room together. They have not removed the third bed from the room since his death.

Arthur's home. The military contends that Arthur died of a brain tumor. Irina and Smbat suspect foul play related to the narcotics story their son recounted. Among other inconsistencies during the investigation, the autopsy did not produce a tumor.

Gohar Ohanjayan's son Tigran died in 2007 while serving. During his last three months of service he complained that the commanders would hit him. The military says Tigran ran into a live wire and was electrocuted. The Ohanjanyan family believes their son was killed.

Gohar: "My son Tigran was born in 1988. I remember lying in the hospital listening to the hundreds of thousands of people outside demanding Armenia's independence from the Soviet Union."

Gohar: "My son was 12 when we decided to move to Russia. We could not make ends meet here in Armenia. One day Tigran saw Armenia's defense minister on TV talking about military service. That's when he decided to return to Armenia to serve."

While serving, Tigran recounted that a younger, weaker soldier was being hazed by the officers and was hit. Tigran had stepped in and criticized the officers. The Ohanjanyans believe their son's death was related to this incident.

Tigran's bedroom. Gohar: "Since we were in Russia, our family members would visit Tigran at the base. On August 22 they noticed once that his eye was bruised and bloodied and that his fists were damaged. Eight days later our son was dead."

Tigran was a skilled judoist and had received numerous medals and accolades in judo.

Tigran's boxing gloves.

The Ohanjanyan family home.

Tigran's judo medals.

A year after Tigran's death, Tigran's father (left) was attacked twice by a group of men who hit him and warned him to stop protesting his son's death.

Gohar: "It's so hard not to know what happened to my child." Although the military's official position is that Tigran was accidentally electrocuted, no electricity was found in the area where he died. The Ohanjanyans continue to seek the truth in their son's case.

Meguerdich Meguerdichian sits next to the bed where his son Jora died in 2012. While serving at the Yeghnikner military base, Jora was severely beaten and fell into a coma. He later died at home in Lousakn village.

No one has been held responsible for Jora's death. The Meguerdichian family lives in abject poverty and has not received any aid from the government.

Jora's mother Gohar breastfeeding her youngest child. Jora was her eldest. She has four children remaining - two of them boys, who upon their eighteenth birthday will in turn be required to serve in the military.

To learn more or to get involved with the issue of non-combat deaths in Armenia, please connect with the following people/organizations: Lala Aslikyan, Tsovinar Nazaryan - Army in Reality Civic Initiative | Zhanna Alexanyan - Journalists for Human Rights | Sona Ayvazyan - Transperancy International